Scapi Magazine Chicago

My interactive sound art website Laughing Web Dot Space was featured in a very thoughtful review of the Entanglements exhibition curated by Chelsea Welch and Iryne Roh of Her Environment, and on exhibit at the Yards Gallery in Chicago in January-February 2019.

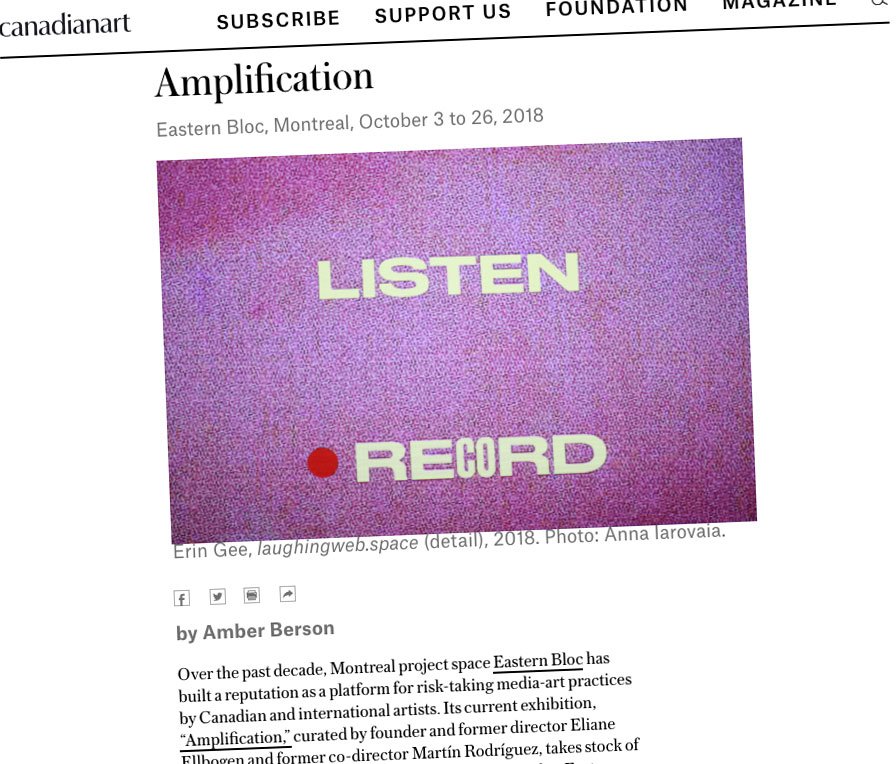

“Now that we’re all agreed that harassment is no laughing matter, let’s stop by Erin Gee’s #metoo resonant Laughing Web Dot Space—a virtual “laugh-in” featuring survivors of sexual violence. Attendees were invited to don headphones and listen to an overlapping chorus of victims laughing and/or contribute (anonymously) their own laughter. The maxim “Question your laughter” came to mind, as I thought of both the violent and cathartic valences of joining in laughter. My favorite element of this installation was the way it built in consent, in the form of a STOP button. “

-NOA/H FIELDS